Remember when I said:

Well…

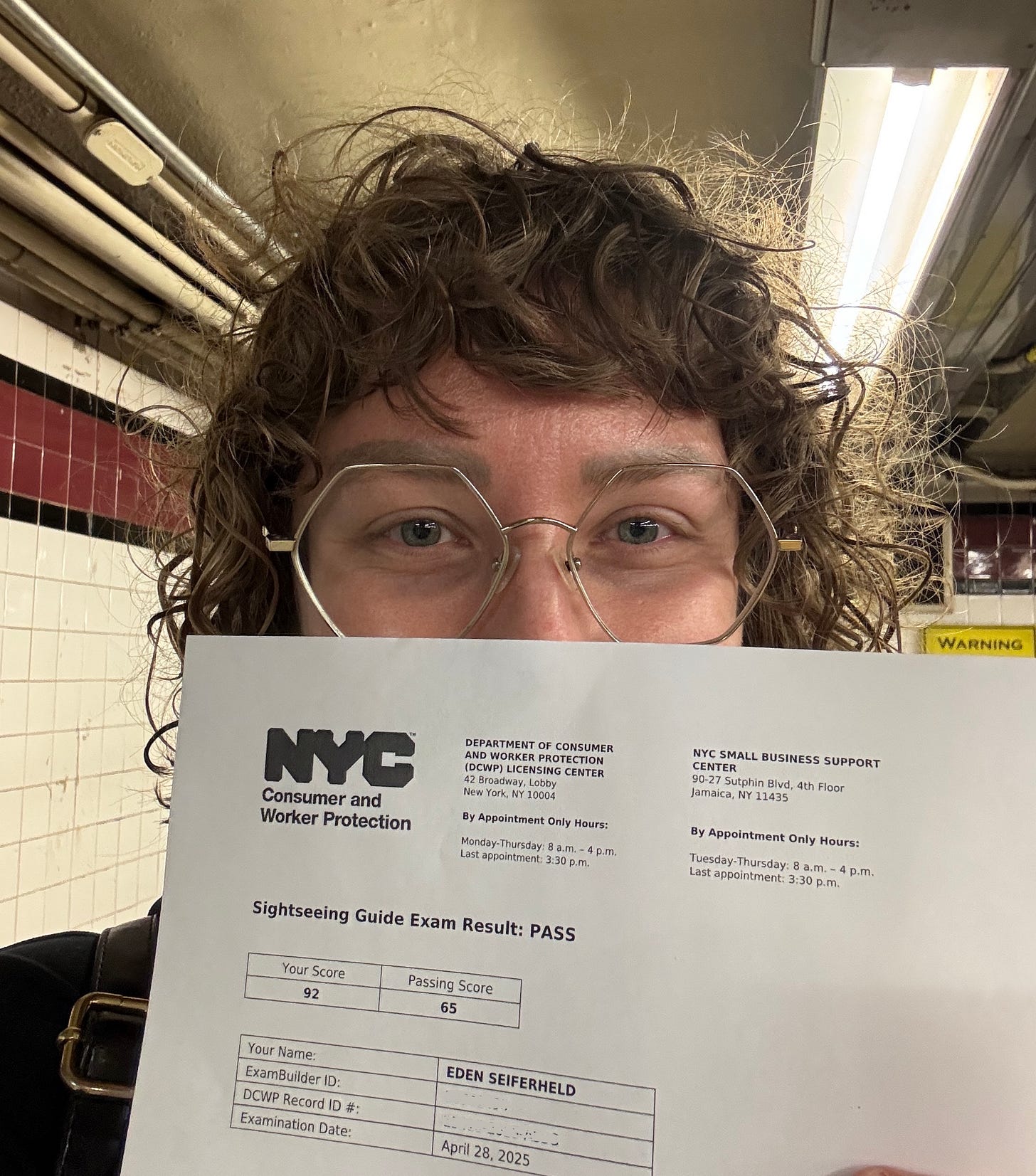

Thank you for your patience while I took a much needed break to focus on some personal goals. I’m very happy to report that I fuckin did the thing 👏

That’s right, you may now refer to me as Licensed NYC Tour Guide Eden. Rolls right off the tongue, doesn’t it? This has been a goal of mine for a couple years now, and I don’t set a lot of personal goals, so it felt really nice to do something for me. I didn’t really think too far ahead as to how/when I’ll give tours around the city, but if you’ve been wanting to walk around and have someone say information at you, I’m ya girl! Reach out and we’ll plan something.

The other thing I took time off to do was develop my Stuff in Sidewalks (in SoHo) tour for Jane’s Walk. I gave 3 (sold out!) tours last weekend, I am exhausted, and I had so much fun. Thank you so much to all of my IRL friends and newsletter friends who showed up; I hope you enjoyed the tour and learned something new. And hello to all of the folks who made their way to BCLF after taking me tour - I’m so happy you’re here. If you weren’t able to attend my Jane’s Walk you’re in luck because this week’s issue is basically a mini version of that tour. Wanna experience the IRL version? Well now you can because I am a licensed tour guide - hit me up and let’s make it happen!

And finallyyyyy a big shoutout to my newest paid subscriber ! Sheri subscribed right before I went on hiatus so thank you, Sheri, for being super patient. And a big welcome to for subscribing after going on my walking tour :)

Stuff in Sidewalks (in SoHo) - A Walking Tour

My philosophy towards history is that it’s not enough to just know the facts - anyone can google who lived in a building or the date that something happened. To really understand history, you need to learn about how all of the pieces connect. Who lived in that house and why and with whom and where did they live before and how did they end up there? What happened on this day and why did it happen at that time, in that place, and what were the lasting effects? I could easily point out landmarks in SoHo and rattle off facts, but I think it’s much more interesting to look at artifacts that may seem insignificant, but are actually indicators of the history of the area.

Case in point - stuff in sidewalks. Sidewalks are permanent-ish, so they’re actually pretty good at immortalizing moments in time. Have you ever left your handprint in wet cement and written “eden wuz here”? Probably not because my name is Eden and that would be weird for you, but you get what I mean. SoHo has actually gone through quite a transformation over the years. Right now it’s an area full of stores with bags I can’t afford and art I’ll never own, but this neighborhood wasn’t always the designer capital of NYC. On this tour of SoHo we’ll cover 3 different eras of the neighborhood - the Cast Iron Age, the Art Revival, and a secret third era that you have to read until the end to find out 😉

➡️ Stop 1 - Puck Building @ 295 Lafayette St

💡 Item of Interest: Vault Lights

New Amsterdam (pre-NYC) was colonized by the Dutch in the early 1600s. While folks initially lived in Lower Manhattan, eventually that area became overcrowded and those with the means ($$) moved north to the “suburbs” of Tribeca, SoHo, and eventually as far north as the Dakotas…aka the UWS. This migration is a familiar pattern that we still see today: rich folks move to escape overcrowding, businesses follow to make $$, lower class workers move to supply labor, the people who originally moved move again to escape overcrowding, rinse and repeat. Eventually after all of the turnover, the area left behind usually becomes industrialized and sometimes simply gets paved over and lost. And that, in a nutshell, is the story of SoHo, as well as the story of NYC at large. But for our purposes, I want to look at what the vault lights tell us about one particular era in SoHo - the Cast Iron Age.

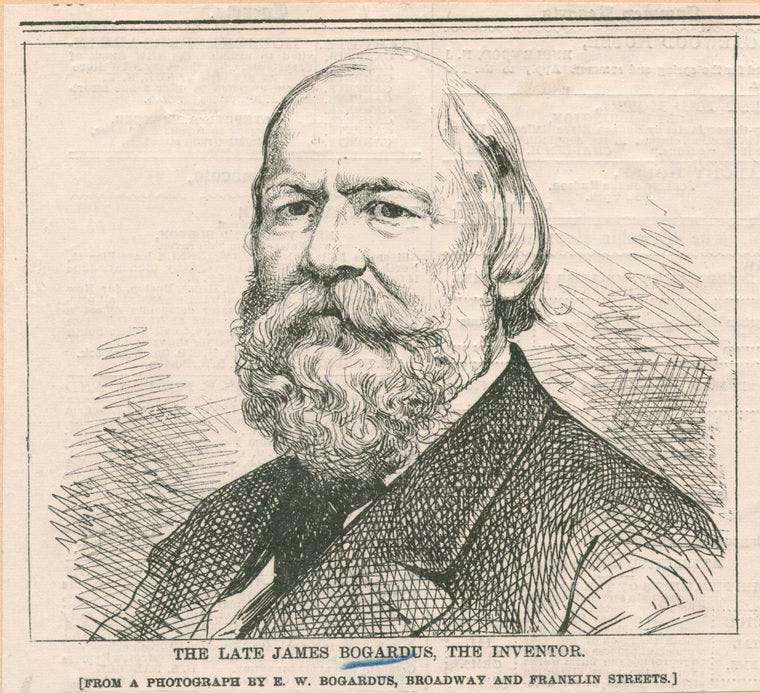

The vault lights here are an indicator of an innovation in building materials during the mid-1800s. Homes in New Amsterdam were first built with wood, which burned down (over and over again). Eventually brick was used, which proved durable, but heavy. Brick buildings required a lot of load-bearing walls which meant buildings could only be 3ish stories tall, interiors were cramped, and windows were tiny. It’s these brick buildings that first sprang up in SoHo when those initial folks moved out of Lower Manhattan and to the “suburbs.” But then along came James Bogardus in 1848 with a revolutionary new idea - build it out of cast iron!

Cast iron was lighter than brick and could provide strong structural support. Now, buildings could reach 6 stories and add large windows. Parts could be easily molded to create stately columns or intricate detailing. These fancy bits could be prefabricated and reproduced in scale, allowing folks to build their dream home from a catalogue. These large, airy, bright buildings became the perfect structures to house department stores and the advent of cast iron is a direct precursor to the steel curtain wall skyscrapers that span Manhattan’s skyline today.

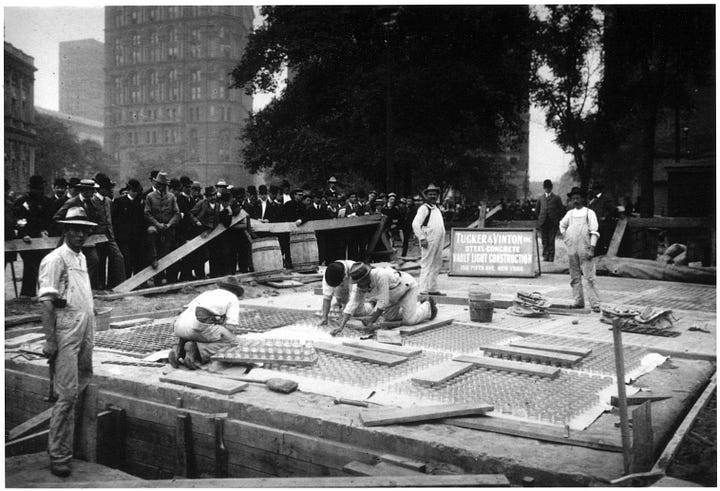

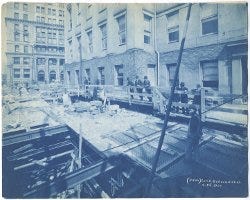

By the time the Cast Iron craze took SoHo, many of the tenants along Broadway were businesses and department stores that took full advantage of the increased square footage that cast iron allowed them - and that included the basements. Landlords love being able to squeeze out as much rent as possible from tenants (some things don’t change), so they really wanted to be able to rent out those subterranean spaces. But it was dark down there and Manhattan had burned down enough times already that folks realized bringing lots of gas lamps into an enclosed space was a bad idea. Electricity wouldn’t gain wide usage for another 50 or so years, so folks needed to figure out a way to bring light into those basements to make them usable. They ended up taking inspiration from a process sailors had been using on ships for years and soon vault lights were born!

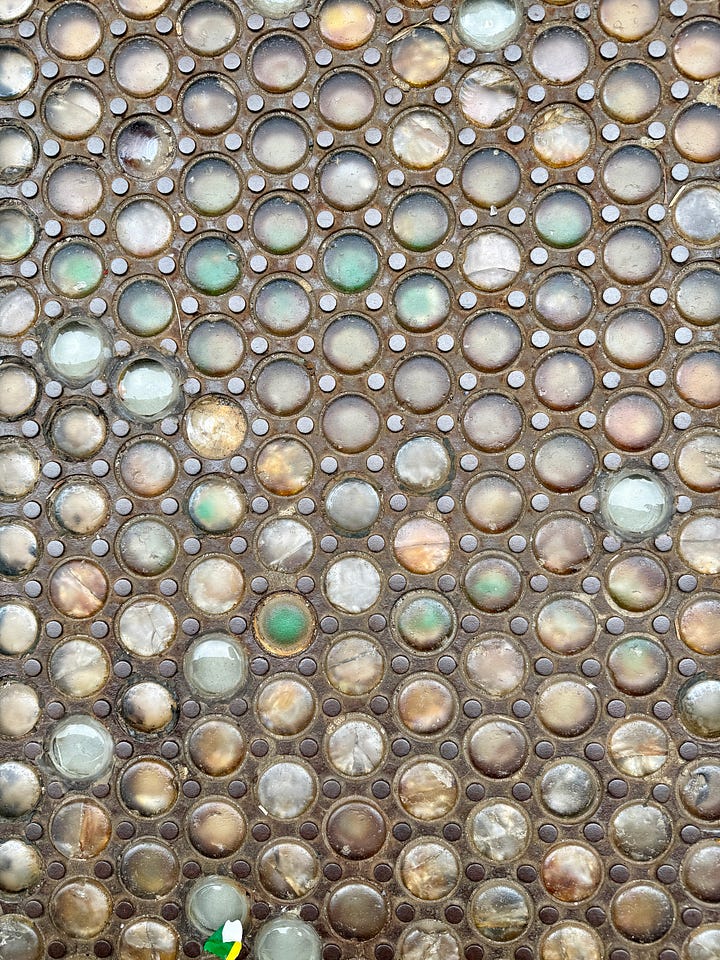

Coinciding with the mid-1800s Cast Iron craze, Thaddeus Hyatt patented Vault Lights in 1845. He embedded glass prisms into cast iron panels and inserted them right into the sidewalks. The prism shape allowed light to extend further into the basement spaces and was revolutionary in bringing NYC’s underground to life. When the first subway lines would open in 1904, vault lights were used to bring sunlight onto the platforms, which made standing in what I know was a stuffy ass subway station much more bearable. In the photos below, you’ll notice that some of the glass circles are various shades of green and purple, in addition to clear. This is because glass manufacturers often mixed manganese dioxide into their glass to stabilize the material. However, as the manganese in the glass was exposed to UV rays over time, the glass oxidized and turned various colors. While a good amount of the vault lights in SoHo today have either been restored (expensive) or covered up with steel panels (cheap), you can tell which ones might still be original by how purple they are. It’s not a fool proof system because sometimes during restorations they’ll actually replace the glass with purple lenses to match the oxidized ones, but it can be a pretty decent indicator of age. While walking around, I’ve found the most colorful vault lights on the western edge of SoHo and into Tribeca.

A quirk of the vault light system, though, was that it rendered many of SoHo’s sidewalks hollow. Because of this, many of the sidewalks in this area are treeless; any trees in the neighborhood are in above ground planters since nothing can go in the ground. It’s one of those things you don’t notice until you do and then you can’t stop seeing it. You’ll also see signs reading “Hollow Sidewalk - No Vehicles” because the sidewalk will quite literally cave in if too much weight is put on it. This actually came to pass on one occasion in a pretty gruesome way - during the 1911 fire at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, as people desperately flung themselves out of the buildings to escape the flames, bodies could be seen falling right through the ground.

Eventually cast iron was no longer in vogue; a big reason it was phased out was that, like wood, it was great at burning down in fires. It also had to be frequently repainted to avoid rusting. From 1900-1960 SoHo fell into a decline and earned the nickname Hell’s Hundred Acres (because of all the fires). The manufacturers that were left around this time moved to the outer boroughs because it had become too expensive to exist in Manhattan (sound familiar?) and the buildings they left behind were unsafe and run down. In the 1960s Robert Moses actually tried to build a highway through SoHo that would connect the Holland Tunnel to the Williamsburg Bridge - the Lower Manhattan Expressway (LOMEX). Public outcry, spearheaded by none other than Jane Jacobs, successfully quashed this plan which would have absolutely destroyed SoHo, Little Italy, and other neighborhoods nearby. Following Robert Moses’ LOMEX defeat, the area would be designated as the SoHo Cast Iron District by the LPC in 1973 and the neighborhood would begin to welcome a new demographic: artists.

➡️ Stop 2 - Guerilla Art @ Prince & Broadway

💡 Item of Interest: Ken Rock’s ‘One Line’ sidewalk engraving

Art is one of those things that no one can seem to decide on: is that banana taped to the wall considered art in the same way that an Impressionist painting is? Why do we simultaneously value art (with pieces selling for millions) and devalue it (offering to pay for design work “in exposure”)? I believe that art is something intrinsic to the human experience; it’s how we express our innate feelings and fears and desires and it’s something every human should be allowed to experience. Whether we’re doodling while on hold, taking a pottery class, or baking a cake, we are all engaging in the creation of art in some way because we want to be surrounded by something beautiful.

When sculptor Ken Hiratsuka arrived in NYC in 1982, the area was mostly inhabited by the artists who moved into and renovated the derelict buildings left behind when industry moved out. The spacious buildings with giant windows turned out to be the perfect studio spaces to hold large canvases and sculptures and we owe a lot to the artists who moved in and put in the work to make these structures somewhat livable. Hiratsuka had just graduated from the Musashino University of Art in Tokyo and came to NYC after receiving a fellowship from the Art Students League. What better place to make art and experiment with styles and mediums than in a neighborhood full of scrappy artists?

Hiratsuka came to NYC with a one way ticket because "New York is international, New York has no rules," he said in explaining his desire to escape the rigid art training common in Japan.

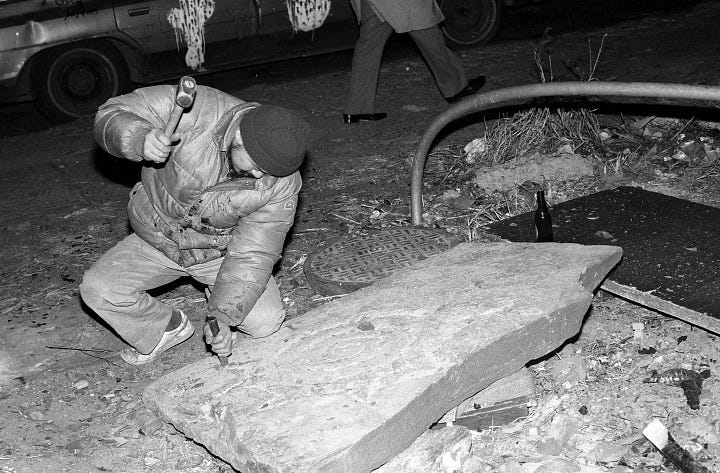

He would soon earn the nickname “Ken Rock” because of his preferred medium (rocks) and desire to carve one continuous line that never crosses itself in stones around the world - a style that was referred to as "Keith Haring meets prehistoric petroglyph." When he arrived in 1980s NYC, the city was covered in graffiti so he figured if people were making markings on buildings and trains, then why not add a little flair to the sidewalks? His earliest sidewalk carvings were complete guerilla works of art a la Banksy; he didn’t ask for permission to carve the sidewalk (who would you even ask?) which did result in him getting stopped by cops occasionally and arrested once. And these were carvings - Ken did not draw lines in wet cement, he used a hammer and chisel to create his sidewalk etchings like a total badass.

Ken Rock soon became a fixture in the 80s NYC art scene and you can find a bunch of other works by him in the neighborhood. His first carving is a few blocks away on Prince St between Lafayette and Mulberry and in 2008 he received a commission from Tony Goldman to create “River”, a 100-ft long carving in front of 25 Bond St. We didn’t visit River on the tour, but it’s absolutely worth seeing because once you realize that the entire thing is a single line you gain a much deeper appreciation for the work. Goldman will also pop up again; he was a real estate developer and turned out to be a pretty solid patron of artists in the area (he’s also the guy who launched the Bowery Mural, the ever-changing wall at Bowery and Houston).

Ken represented the early, rag tag group of artists that simply had to make art for art’s sake and were willing to live in crumbling buildings just to be surrounded by other creatives. They sought to beautify their chosen home and would eventually make SoHo the center of the art world for a few decades to come.

➡️ Stop 3 - Commissioned Sidewalk Art @ 112 Greene St

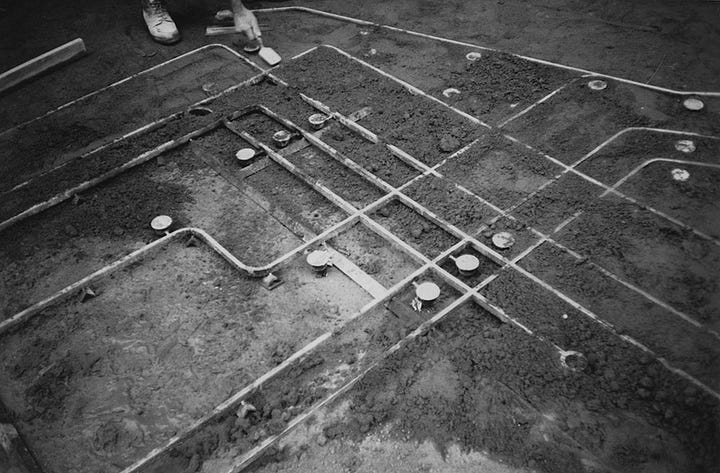

💡 Item of Interest: Francoise Schein’s Floating Subway Map

Born in Belgium in 1953, artist Françoise Schein studied Urban Design at Columbia University. A lot of her art focuses on how people mentally map cities and the layers of meaning within urban spaces. She has art in transit systems around the world and each of them has become designated local landmarks. To Schien, a subway system is “the most democratic place into which one can engrave philosophical concepts to address to the people. It provides a liberty of movement that we often forget even though without it, our societies can’t function anymore.” SoHo was still pretty run down in the early 1980s and Tony Goldman wanted to spruce up the area around his new building at 112 Greene St. So when he approached Schein to create a piece of art in the sidewalk, a map of the NYC subway system was the natural choice.

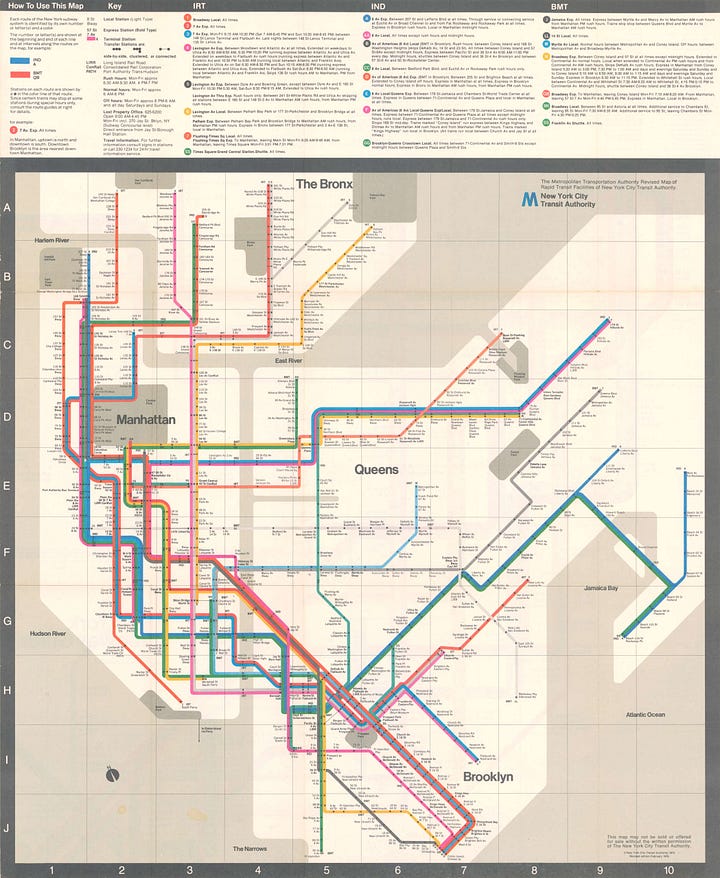

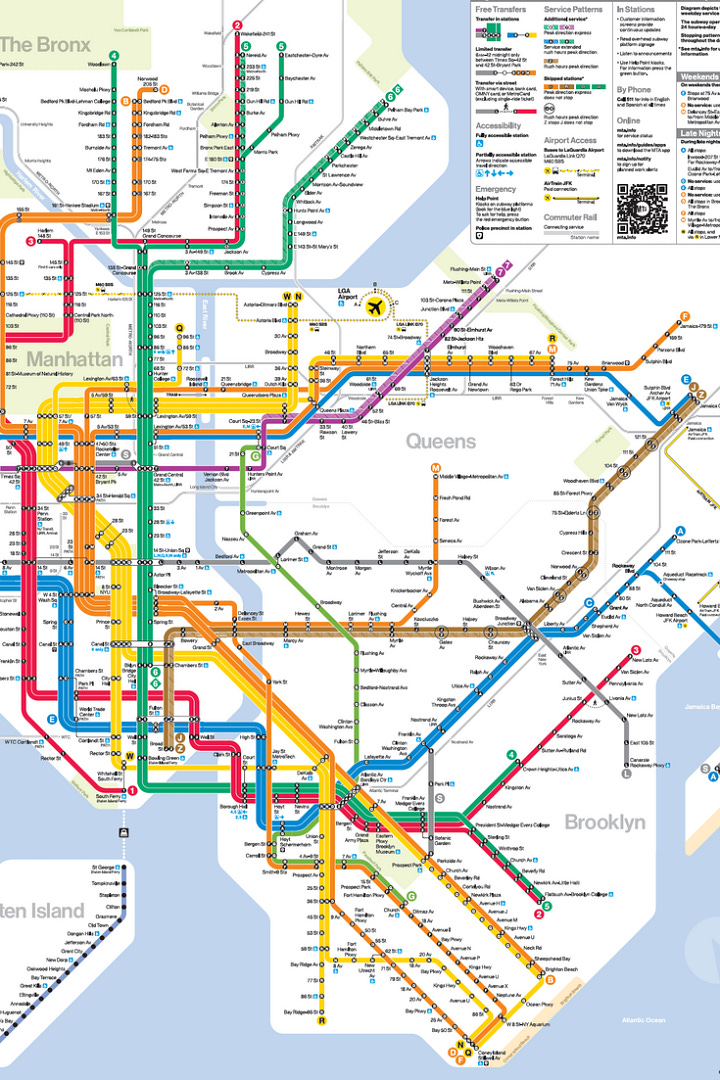

The entire piece is 90x12ft long and includes 156 subway stations, accurate as of 1985. If the sidewalk map looks familiar, that’s because it was likely based on one of NYC’s most famous subway map designs which would have been the current one at the time - Massimo Vignelli’s Unimark Map. Compare the sleek curves in the sidewalk map to the ones on the printed map - the influence is definitely there. This map is so famous it’s in the freaking MoMA and our recent subway map redesign also bears a striking resemblance:

Schein’s subway map was made of stainless steel bars, terrazzo flooring, and glass discs (blown by the artist herself). The original design also had lights embedded into the ground, though it appears the lights are no longer functioning. The materials and design of the sidewalk map are absolutely an homage to SoHo’s cast iron past, right down to the industrial looking bars and the glass discs echoing vault lights. The map only contains Manhattan subway stations and Schein lamented that she simply couldn’t fit Brooklyn and Queens into the sidewalk (sorry to The Bronx and Staten Island, you were never even a thought in her mind).

Schein’s subway map commission came about during a turning point in SoHo’s history. Suddenly, developers were paying to have art placed in the neighborhood to make it a more desirable place to visit. Throughout the 80s and 90s, SoHo refashioned itself as a trendy, high end neighborhood and soon the luxury brands would set up shop in the buildings that the artists worked so hard to turn into homes. The artists were priced out of their neighborhood and moved to another neighborhood known for having large, vacant lofts - Williamsburg. And we all know how that went…

➡️ Stop 4 - A Small Window Into the Past @ 139 Greene St

💡 Item of Interest: Belgian Block and the Anthony Arnoux House

At this stop, we took a moment to go back in time to the early 1800s when SoHo was a suburb full of little brick buildings on belgian block streets. Yeah that’s right, I said belgian block, not cobblestone. I’ve written about Belgian block in BCLF before and that’s because it’s one of my favorite “did you knows” to rattle off. When folks see streets like this they automatically refer to it as cobblestone but apparently the world of stone paving spans far and wide and the stones we find in SoHo are actually Belgian block. Strangely, though, they are not from Belgium. So what’s the deal?

The difference is in the shape & placing of the stones. Cobblestone uses uncut rounded stones and needs additional filler, like dirt, to fill out the crevices. This makes for a pretty wobbly path. Belgian block uses granite that has been cut into rectangular shapes that fit together much nicer (basically, ground bricks). Because they fit together neatly, very little filler is needed and they create a much smoother surface.

Similar to how cast iron was an innovation in building materials, Belgian block was an innovation in street paving. What began as dirt roads would become cobblestone, then Belgian block, and eventually asphalt by the early 1900s when cars came into the picture. Belgian block provided good traction for horseshoes, so it was a popular during the time of horse drawn wagons. The stones used were purposefully cut to the relative width of a horseshoe - between 4 and 5 inches. This allowed horses drawing heavy loads to secure a firm foothold in the joints between blocks. Today, the most common Belgian blocks in New York City are about 4 inches wide by 7 inches long – a type known as the “Manhattan standard” which date from 1912 to 1938.

In fact, most of the Belgian block in SoHo today is not original and a lot of it has disappeared altogether. In 1949, Manhattan had 140 miles of Belgian block streets but today we only have about 15 miles worth. Mercer and Greene in particular were paved over with asphalt but were refitted with Belgian block in the 1990s when the Department of Transportation excavated them to repair water pipes as ”an opportunity to retain some of the old elegance of our city,” according to a city commissioner. Along with SoHo, some of the largest concentrations of Belgian block in the city can be found in Tribeca, NoHo, and DUMBO. The Belgian block in DUMBO, while better than dirt roads or cobblestone, has been deemed non-ADA compliant, so there’s actually a project underway to make it more accessible while retaining the old-timey look of the neighborhood.

Despite there being Belgian Block all around SoHo, I chose this spot as a stop for its unique vantage point into the past because of one particular home on this block - the Anthony Arnoux House at 139 Greene St. This brick home dates back to the 1820s and if you imagine this little plot without any cars or the cast iron buildings on either side, it’ll give you a good idea of what Greene St looked like during its days as a suburb.

By the late 1800s, the Arnoux family had left their home as industry moved in, and then out, as SoHo became a pretty grungy neighborhood. The home was a brothel for a few years and then changed hands a bunch more times to house various businesses that ended up doing a number on the poor building. A hole was cut right into the parlor to fit a shipping dock and the interior details were trashed.

In 1973 the home was sold to Peter Ballantine and he’s spent the last 50 years slowly fixing up the building. Because the building is part of the SoHo Cast Iron Landmark District, there’s lot of red tape involved in making changes, which likely accounts for the slow pace of the restoration. Interestingly, Mr. Ballantine has lived in the building this entire time!

➡️ Stop 5 - Manhattan before Manhattan @ Houston & LaGuardia Pl

💡 Item of Interest: Time Landscape

The final stop on the tour is a living artwork right on top of the sidewalk that takes us back to NYC before the Dutch arrived! And yes I know we’re technically north of Houston St now and no longer in SoHo, but it’s my tour so I make the rules. I must have walked by this street corner a million times until I realized the little sign inside the fenced off area that reads “Time Landscape.”

“As in war monuments, that record of life and death of soldiers, the life and death of natural phenomena such as rivers, springs, and natural outcroppings needs to be remembered. Climate change has been an evolving crisis in our society, and my art exposes the gravity of the issues. Each of my artworks echoes an understanding of the fragility of our environment.” -Alan Sonfist

The artist, Alan Sonfist, proposed the creation of this living sculpture in 1965. He was interested in creating a different kind of memorial; instead of plopping a marble statue (of yet another white man war general) on a street corner, why not work with the natural materials already available? He wanted to create “living art” that would change over time and sought to establish a slowly developing forest that represented the Manhattan landscape inhabited by Native Americans and encountered by Dutch settlers in the early 17th century. This was incredibly timely as interest in the natural environment had recently come to the forefront and the first Earth Day would take place in 1970. But that didn’t mean the project would come together easily.

“When I created the landscape, the lower officials of the city were all afraid of what would happen if I created a wild forest in the city of New York,” Sonfist noted. To get permission to build it, Sonfist had to agree to put a steel fence around the space because officials were scared of the danger of “wildness” in the city and the plants’ potential to overtake the surrounding area. Like oh no, there are flowers everywhere, how horrible. But ever the optimist, Sonfist charged ahead and took the restrictions in stride:

“At first I objected, but then I realized the city was contributing to another way of looking at a forest,” Sonfist said. “Actually, I kind of like the idea of the fence around it now because it creates a viewing arrow into the forest, and that’s a very special way of looking at it.”

And so after extensive research on New York’s botany, geology, and history, Sonfist and local community members used a selection of native trees, shrubs, wild grasses, flowers, plants, rocks, and earth to plant the 25x 40ft rectangular plot at the northeast corner of La Guardia Place and West Houston Street in 1978. Sonfist’s initial concept was to portrayed the three stages of forest growth from grasses > saplings > grown trees.

The southern part of the plot represented the youngest stage with birch trees and beaked hazelnut shrubs, with a layer of wildflowers beneath 🌿

The center features a small grove of beech trees (grown from saplings transplanted from Sonfist’s favorite childhood park in the Bronx) and a woodland with red cedar, black cherry, and witch hazel above ground cover of mugwort, Virginia creeper, aster, pokeweed, and milkweed 🪻

The northern area is a mature woodland dominated by oaks, with scattered white ash and American elm trees 🌳

Among the various other species in this mini forest are sassafras, sweetgum, tulip trees, arrow wood and dogwood shrubs, bindweed and catbrier vines, and violets. These forest stages have all blurred now as new plants have made their way into the landscape, but that was the whole point. Sonfist noted that his “art is about change, and as the world changes the time landscape changes as well,” so he expected this to happen and welcomed it.

The Time Landscape seeks to remind us of the land that we all inhabit today. It’s a bit like a mini National Park in the middle of Manhattan, a ‘what if’ scenario that depicts what the island could have been had we just left it all alone.

And so our tour ends where it all began - Manhattan as it was before the idea of a sidewalk even existed! I hope this [written] walking tour will inspire you to look around at the mundane and the little details and consider how they relate to the bigger picture. At the very least, I’m sure you’ll be looking down a lot more (but please also remember to look up, I will not be held responsible for any accidents that occur while walking around NYC).

🚨🚨🚨🚨🚨 Next week we’re finally at BCLF 100 so this is your absolute last chance to submit your NYC story to be featured. What the hell are you waiting for??!! If you’ve been thinking “I don’t know if anyone wants to hear my story” I promise you that you’re wrong - I want to hear it. 🚨🚨🚨🚨🚨

This was all fascinating. Thank you!

I'm sorry, the fact that the left pic is Ken Rock's first sidewalk art is OFFENSIVE. Aren't you supposed to be bad at things before you're good?!!?